by Kathryn Tsui, 9 Jul 2024 (republished from Kathryn Tsui: cloud ribbon)

Wailin Elliott and I met at the first Chinese New Zealand Artists Hui, held in 2013 at Corban Estate Arts Centre, where I was the curator. Ten years later I was able to visit Wailin while on a residency at Driving Creek Railway and Pottery. Wailin Elliott is an artist I admire and can relate to as there are distinct parallels between how she forged her practice and the path mine has taken.

We both moved to Te Tara-o-te-Ika-Māui Coromandel Peninsula with young families, share the experience of being artists who work in craft practices, and come from Cantonese families who ran fruit shops in Tāmaki Makaurau (her parents and my maternal grandparents). I was interested in hearing more about her endurance as a maker.

Wailin has been an active artist for seven decades – making ceramics, paintings and weavings, and printing books. She epitomises a sustained creative practice, although one that is not widely known. I am grateful she was so willing to contribute her time and thoughts for this project, an insight into an icon!

We spoke in May 2024

Q: With your sister Eva Ng being a writer, was art important to your family, growing up?

A: Our mother was very creative, her embroidery was exquisite and she was a talented sewer. My sisters, Eva and Ehlin, were taught by her to embroider and darn, but I was only a four-year-old when she passed away. She also had her own fruit shop across the road from our father’s fruit shop on Broadway, Newmarket, which she had to manage as well as three young children.

But it was at Epsom Girls Grammar School (EGGS) … there were so many clubs you could join during lunchtime and there was nothing my father could do to stop me joining the leatherwork club, the basketry club, the camera club and the embroidery club, because it was in school time.

Q: Does your Chinese heritage come across in your work? Or is it something you have tried to avoid?

A: Because I grew up as a Chinese girl, of course I was influenced by the pottery I knew and used in the home – rice bowls and serving dishes – and I used to spend a lot of time on the weekends at Auckland Museum in the Oriental department, looking at the celadon ware and traditional shapes. The museum was close by and, as children, Eva, Ehlin and I spent much of our free time there on the weekend if we weren’t working in the fruit shop.

You just can’t help your ethnic background. I was a potter and I potted the things I knew until I knew differently.

Q: Did you know Guy Ngan and Ron Sang? Were there any other Asian creatives in your circle?

A: Although I knew Ron Sang and we moved in the same circles, he never showed the slightest interest in my pottery. Guy Ngan lived in Wellington and was somehow related to people we knew, but I never met up with him.

Diana Wong, who was older than we were, was an artistic girl who was looked upon by the Chinese fraternity as being different. She produced books with photographs of her friends. I did admire her disregard for convention.

Q: When did your interest in making pottery begin?

A: I didn’t take art at EGGS, I took an academic course that did not include art. May Hardcastle (née Smith), an art teacher at EGGS, allowed me to attend one of her fourth-form art classes in my free period and she encouraged me to pot.

One of my friends at EGGS was doing Fine Arts Prelim to apply for entry into Elam and one of the things she made was a clay dish. She slipped it with an iron slip and sgraffitoed a pattern all over. I thought to myself, “It’s beautiful.” I wanted to be able to do that.

The school library was large and I could indulge in reading without having to pay for a public-library subscription, and it was here that I found Craft Horizons magazines and read Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book, which helped change my life around.

“We dug our own clay, found demolition sites and collected second-hand bricks to build a kiln. We used wood ash from the fire to make glazes.”

Q: In what ways did Barry Brickell encourage your pottery practice?

A: I met Barry at summer school in 1956–7. He was a tutor, along with Len Castle, that year. We dug our own clay, found demolition sites and collected second-hand bricks to build a kiln. We used wood ash from the fire to make glazes. After summer school, Barry and Len encouraged me and so did Helen Mason, though at this time she lived in Wellington.

Barry drew up plans for building a kick wheel for me and found an old wheel which he concreted in, and I had a carpenter, a family friend, who built it for me. It was large and unwieldy, and I hid it from my father in the old shed beside the house. I cleared a space on a heavy bench where I could wedge clay, and potted whenever I could find time. There was no electricity in the shed and no running water, but I made do.

Q: Can you talk about your move with your husband, woodcarver Tom Elliott, to the Coromandel?

A: Barry wanted a piece of land up Driving Creek Road, because there was clay and the terrain was ideal for a railway. The clay was good for potting, but the farmer wouldn’t allow him to take the clay from the property. Our place in Titirangi was too small for our family so we had been looking for a place in the Coromandel, but we couldn’t find one that we could afford and one that we liked. When the piece of land came up for sale, Barry said would we like to buy his place for the same price as he was buying the piece of land. So he got the land and we got his place. We were quite happy. I knew Barry’s villa and I loved it. We moved in 1973. Barry lived with us for a year or more while he was building his place up Driving Creek Road.

“I loved that it was like a village, a country atmosphere. Because in those days growing up in Newmarket was like a little village as well, so it was no different.”

Q: What did you enjoy most about moving to Coromandel town?

A: I loved that it was like a village, a country atmosphere. Because in those days growing up in Newmarket was like a little village as well, so it was no different.

Q: Can you talk about the transition, from making items to sell at Brown’s Mill to making ceramic sculptures, that occurred after moving to the Coromandel?

A: I no longer wanted to make pots that I had to sell at Brown’s Mill (1) to make money. I wanted to make what I wanted to make and not to be influenced by money. When I went to Driving Creek I had the children, who became my models, and I made things I liked. I made ‘peopilics’, as Barry used to call them. I had a wheel in Coromandel and a wheel in Auckland, but I far preferred to make things by hand because of the children. It was far easier than throwing, to make slab and hand pots instead. With hand potting you could cover it with a bit of plastic when you needed to and then go back to it without the pot drying out.

Q: You’ve held a long association with Driving Creek, and you still have a studio there.

A: Well, I had a studio and I worked there. There were always people coming through. Barry somehow drew all those artistic people down and you just made friends with them. Not only potters – painters, poets, writers, conservationists, engineers, all sorts of people.

Tom and I were there from the beginning and then we were general managers. I think it was twenty-five years for me and eighteen years for Tom, seven days a week, up until 2016. It was a wonderful life, we had a wonderful time. It was the first paid job in our married life, before that we were self-employed and lived off what we made and sold.

Q: I didn’t realise you wove until my visit with you in 2023 when you showed me your weaving. Can you talk about your weaving practice?

A: At primary school, in Standard 3 or Standard 4, we had little table looms and we learnt to weave on them. I’ve never forgotten that. Although I didn’t take up weaving again until I got a job at Adult Education, which was part of Auckland University – I was a receptionist and typist. I started weaving again on my breaks in their craft department. I wove in linen and cotton, and I went to W & H Sutherland & Co. in Cook Street for thread supplies. They had books of silk, but I didn’t know anything about silk in those days. When we moved to Coromandel and I was still weaving back then, I had a three-foot wide, four shaft Peter de Moree loom, he handmade these and sold them at Brown’s Mill. But I couldn’t fit it in our home at Driving Creek. I had to get rid of it in the end. I wasn’t using it enough and it was too large.

Q: I also have a Peter de Moree loom! Did you ever consider your weaving practice in the same way as your pottery practice?

A: No, I was never going to have enough time to spend it on weaving. Although if I had a small loom like I had access to at Adult Education, then I would have been quite happy with a smaller loom.

Q: Can you talk about your sericulture, your silkworm-raising practice?

A: I wanted silk for weaving. I raised silkworms for about forty years and planted mulberry trees in Coromandel, three at Driving Creek, and also at our place in Auckland. I was always looking for mulberry leaves, continuously, to feed them. I raised thousands of silkworms. I needed sixty cocoons to make one thread, to make a thread strong enough to weave. Theoretically, I thought, in the winter at Driving Creek I would have time to reel and weave the silk. But it just didn’t work out that way. I stopped raising because my eggs stopped hatching. It was only a few years ago they stopped, I think the eggs were just too old. I was very fond of them.

Q: I know you collect Chinese textiles. Can you talk about your collection and your interest in this area?

A: I have always been interested in articles made of silk. I used to wear a cheongsam (2), I wore them to work and always had a collection of them. I was able to buy some antique Chinese garments from a friend in Kennedy Bay, Coromandel, who had brought them from auctions in England. I also have my mother’s collection of clothes she brought with her from Canton, China. When my father moved house from Newmarket to Epsom we discovered two black lacquer chests of our mother’s. My three sisters and I cast lots for them and I was lucky enough to get the first chest, which contained my mother’s silk clothes, which she wore in China but she never wore them in New Zealand; I used to wear them until I realised how precious they are. In our documentary Two Sisters (3), we bring out that box.

Q: I also got to see your paintings for the first time on my visit. Can you share a bit about them and their subject matter?

A: In 1992 I realised I could paint. What I painted was what I saw in my mind’s eye, not what was around me, it was from memory. I took what I could remember of my past and put it into my paintings to tell a story. Although I haven’t painted for years I am still trying to paint my son’s wedding, which was in 2012. I’m not satisfied with it and would like to paint it all over again. If I don’t have silkworms perhaps I can start painting again. Who knows what life holds for me, because there is also my printing. I’ve just printed and published another book, but not by hand this time. For many years I have been interested in hand-press printing. The first book I hand printed was by my sister, Eva Wong Ng – Shadow Man, a book of short stories that took me four years to produce.

It has been a lifetime of interest in all the things I am interested in.

Footnotes:

- The Mill, commonly known as Brown’s Mill, one of New Zealand’s first collective craft markets, opened in 1968.

- A straight dress with side slits, a standing collar, and an asymmetric opening at the front.

- Asia Dynamic: Two Sisters, directed by Alison Carter (Asia Vision, 1997), https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/Asia-dynamic-two-sisters-1997

Wailin Elliott 黃惠蓮 (Wong Wailin) was an artist best known for her pottery. She was also a spinner, weaver and sericulturist, as well as a painter, writer, printer and publisher. An active artist for seven decades, Elliott was part of Aotearoa’s studio craft movement since the 1960s. Originally from Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, moving in 1973, Elliot has lived in Kapānga Coromandel with her husband, wood carver Tom Elliott. With a studio at Driving Creek Railway and Pottery, Elliott became very involved in the running and development of Driving Creek from the beginning and was a general manager until 2016. She worked in earthenware, stoneware and terracotta. As well as producing studioware such as pots, Elliott is known for her human figures, termed ‘peopilics’.

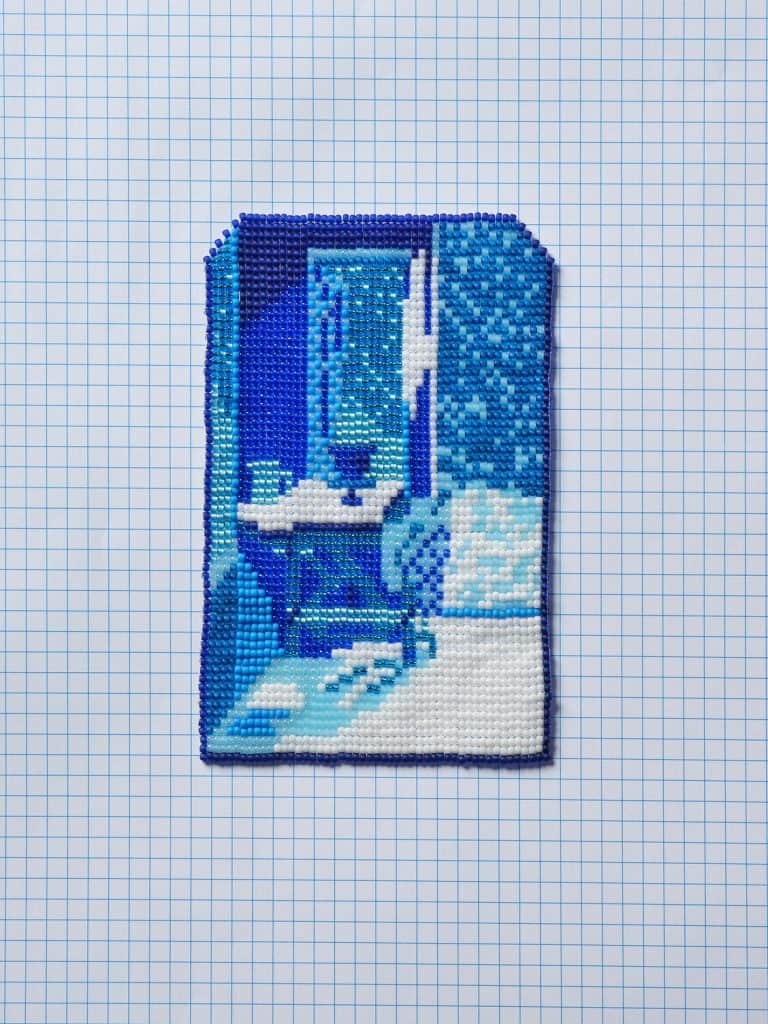

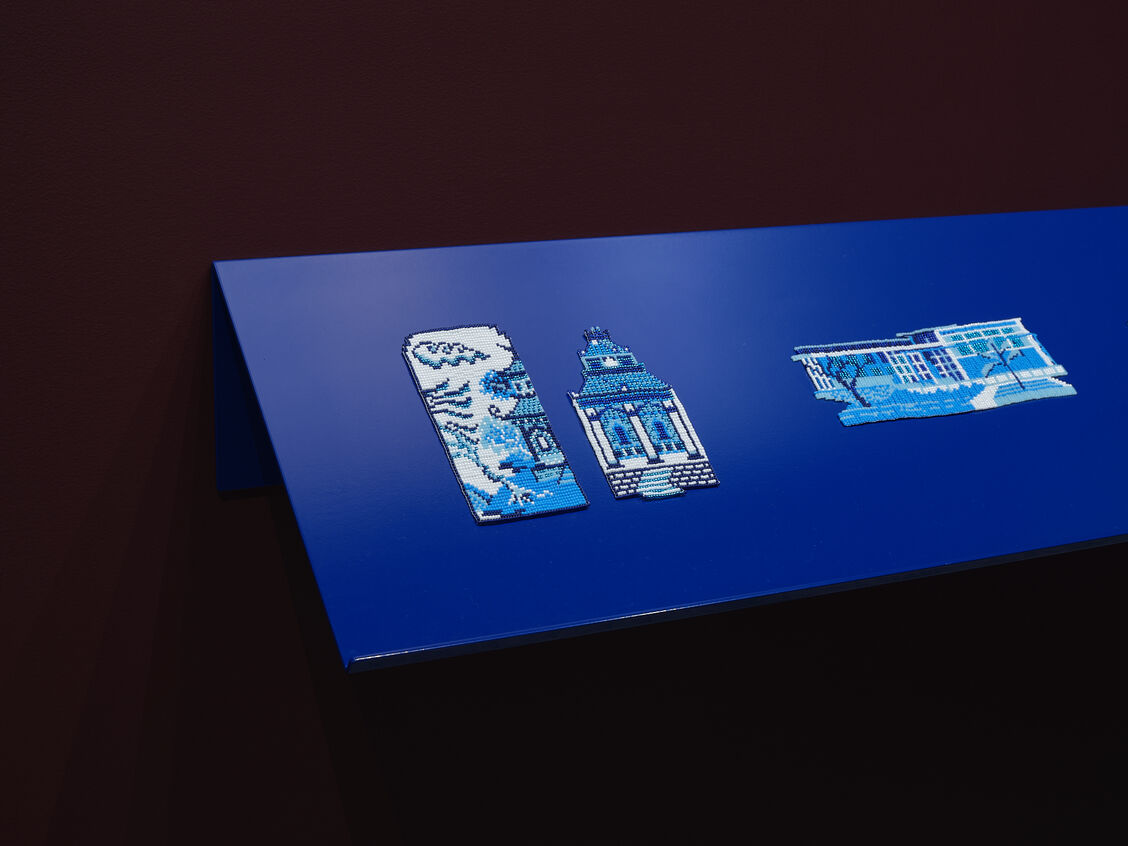

Kathryn Tsui 徐敏貞 (Tsui Mun Jing) is a textile-based artist who works primarily in loom weaving and beading, and currently lives in Tairua, Te Tara-o-te-Ika-a-Māui Coromandel Peninsula. An ongoing thread in her practice is a focus on mass-produced objects and common patterns where Asian material culture has intersected with other traditions and influences. The result is a dialogue between notions of value and embedded sociocultural hierarchies. Tsui’s work is held in the public art collections of The Dowse Art Museum, The University of Waikato Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato and Tūhura Otago Museum. She also works as an arts programmer and was one of the organisers of the first Chinese New Zealand Artists Hui in 2013. Tsui holds a Bachelor of Visual Arts from Auckland University of Technology Te Wānanga Aronui o Tāmaki Makau Rau (2007).

This interview is republished from a companion publication to Kathryn Tsui’s 2024 exhibition cloud ribbon, on show at Objectspace from 15 July to 1 August 2024.

this article and photographs are courtesy of Sam Harnett and the gallery